This Space Left Intentionally Blank

By Ven Loetz

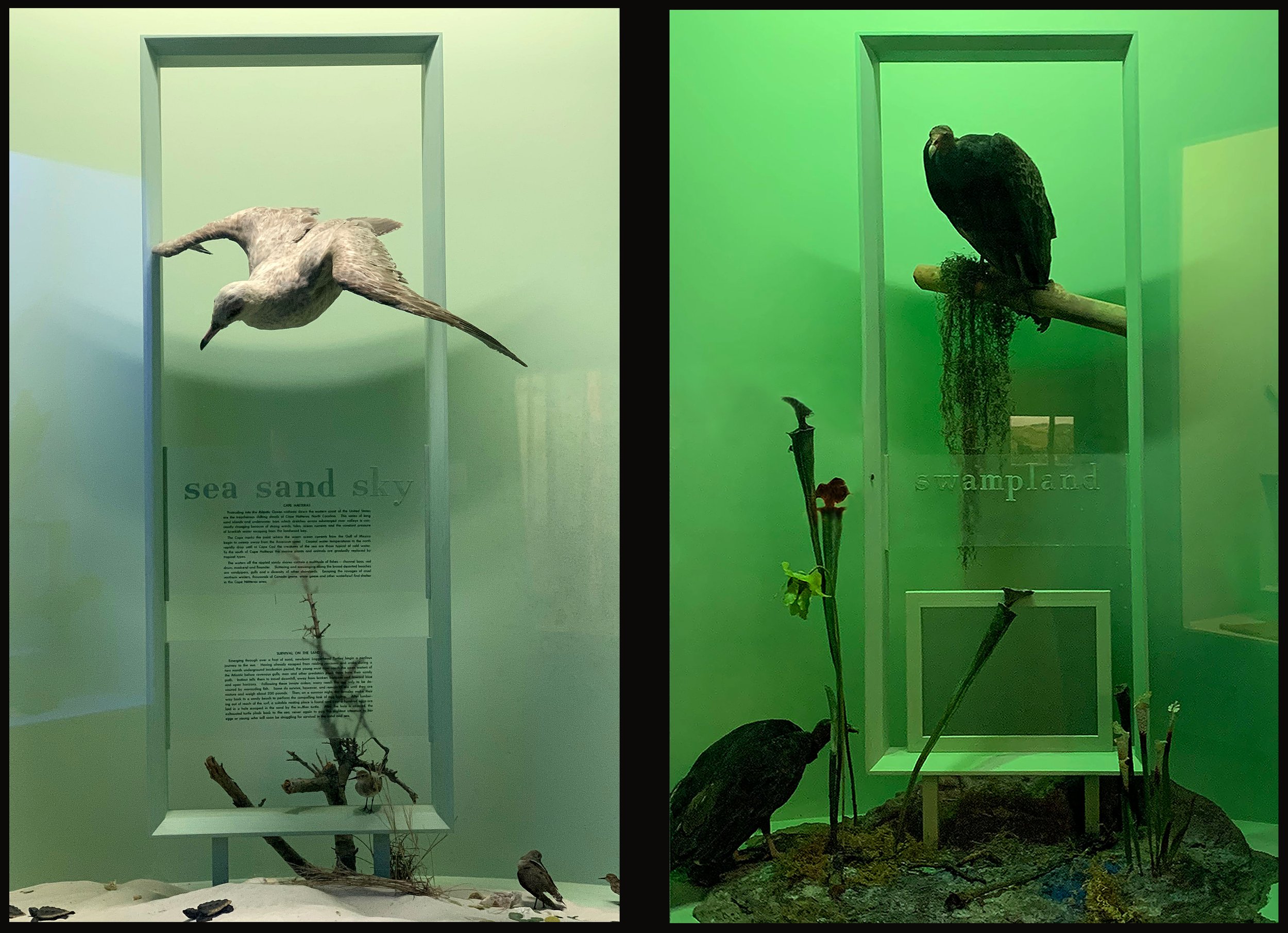

A stunning nature exhibit on MPM’s second floor.

In a museum filled with thousands of objects, many of them set within immersive environments, how does one interpret all of them? How do the objects speak for themselves and when is more information necessary? Just where is the line between “more information” and “TMI”?

As a frequent visitor of art museums, natural history museums, and other sorts of collections, there is a delicate balance between experiencing and learning. It’s an interplay between modes of communication and how the mind processes and integrates information. During my many meandering visits to MPM, I’ve noticed here and there, places where signage is missing or, in some cases, objects are missing but the signs are still present. In a way, the absence is a quiet pause; an invitation to breathe. It leaves us wondering what we might be looking at and leads us to fill in the answers using our own experiences. Take, for example, a beautifully moody display case depicting a “Swampland”. The neighboring cases are clearly labeled with information about the ecology of their contents. Paragraphs explain the organisms of the sea shore or the mist shrouded mountains and how they interact with one another. But the sign frame for the swampland is blank. From my own experience, I recognize turkey vultures and some variety of carnivorous pitcher plants. What else do I need to know about swamps and why has the sign been removed? Was is outdated? Or had it simply come loose from the glass and needs to be repaired or replaced?

Neighboring display cases: one with several paragraphs of descriptive text (left) and one that simply says “Swampland” with a blank frame beneath.(right)

It may seem obvious to some that this little guy (pictured below) is an otter with a fish. Not everyone, though, might know their animals and plants as well as I do. I’m a bit obsessive about natural history and I’m also an adult with many decades of acquired knowledge to draw from. When I visited the museum as a small child, I likely wouldn’t have known a river otter from a beaver or a muskrat. I often overhear small children at the museum asking their parents what something is and sometimes the parents give wrong answers whether signage is present or not.

This large diorama featuring a taxidermy river otter and fish has had both a plaque in front of it removed as well as wall signage (to the right of the diorama). The empty, rectangular spaces remain.

Things get less obvious to me in areas where my own knowledge is lacking. On the third floor, a case labeled “Aymara” holds an assortment of interesting items such as tiny silver spoons with pointy handles. Miniature knitted clothes and a tea set remind me of Christmas ornaments and dollhouse miniatures from my childhood. The case is located in the South America section, so clearly the Aymara people are/were from this part of the world, but there is nothing to tell us what these objects mean or how they were used. I paused to google “Aymara” and learned what Wikipedia has to offer on the subject, but the objects remain mysterious. Are miniatures themselves a part of Aymara culture? Or are these just representations of their traditional clothing shown at miniature scale because of limited space in the museum? Unclear.

This one wall case represents a group of people from South America, but gives no information beyond the label “Aymara”. It’s enough to spark curiosity, but not enough to satiate it.

Looking at the photos collected for this post, it’s lovely how many shades of green and blue appear throughout the exhibits. In some ways, the shades and combinations come off as a bit dated, especially combined with older fonts and those little plastic label letters that were ubiquitous in the mid 20th century. At the same time, the colors are soothing in some spaces and invigorating in others. When taken to the extreme, it’s puzzling to see the use of color extended to places like these backlit signs on the third floor. The shade of green is intense and the number of paragraphs seems an awful lot for anyone to stop and read the entirety of while wandering the exhibits. This particular exhibit also feels a bit redundant given the massive rainforest exhibit on the first floor. This leads me to believe the third floor “Middle American Rainforest” predates the one downstairs. It also shows many of the same stylistic elements that were used in the later exhibit such as sound effects and multiple levels. It extends upward to the third floor mezzanine where the rainforest canopy is full of birds and vines and a wall speaker fills the space with wild sounds.

A large installation that extends through several glass cases and is labeled with backlit signs.

The rest of the mezzanine is made up of more typical showcases of cultural artifacts on shelves. Here we find a miniature diorama made to look realistic, but populated by stylized clay artifacts. Again: there is a strange interplay between when a miniature is the artifact and when the miniature is a depiction of an item’s usage and this case straddles these two realities. A small card in the corner notes “SPECIMEN TEMPORARILY REMOVED”. We are left to wonder what object belongs in this gravelly corner of the landscape. I also hope that one day someone will label my artworks as “SPECIMENS”. How would the artists who made these sculptures feel about this display? Would they be pleased, confused, or perhaps offended?

In this display, the miniatures are the actual artifacts. The note says the object was removed Oct. 2017- Jan. 2018. Is it still missing or was it returned five years ago? If it was returned, why is the card still there? What is specimen 000545? I’m picturing a mischievous clay goat. Prove me wrong.

Since the purpose of a museum exhibit is education, how the information is conveyed is an important consideration. This is not only with regards to how people learn and retain information, but also in how the cultures and ecosystems depicted are affected by the public’s perceptions. Context becomes crucial and when signage is lacking, the viewer’s imagination may fill the empty space with misinformation or stereotypes. But if the signage is overwhelming, viewers may skip over it because there’s little time to read large blocks of text if you’re herding a group of 3rd graders on a field trip. Again, when the children ask questions, the adults may not have time to read the whole sign and may fill in or summarize with misinformation.